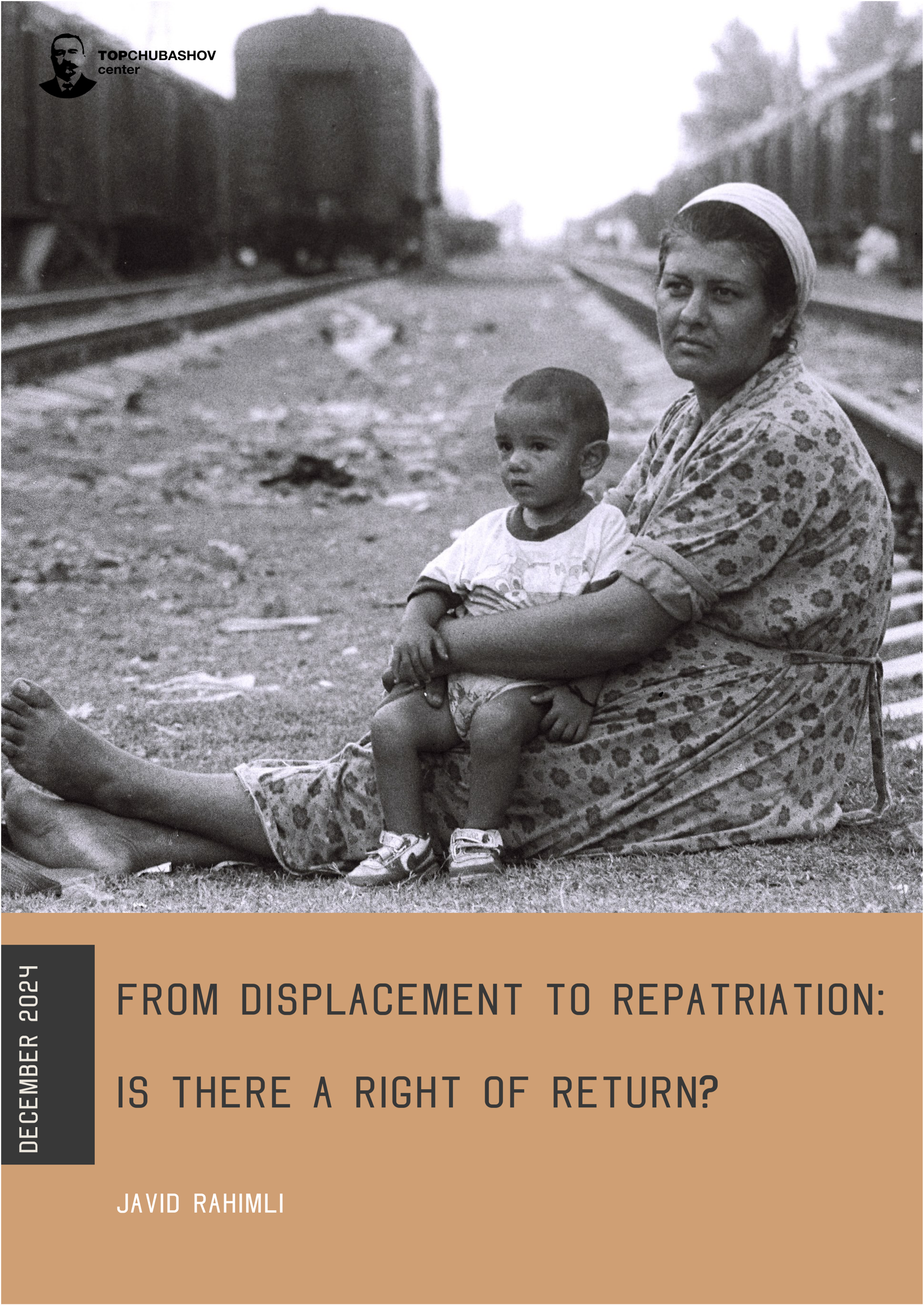

This research examines the legal status of the right of return for forcibly displaced persons under international law, arguing that it has become a norm of customary international law (CIL). Through analysis of treaties, declarations, resolutions, and case law, the research explores the legal foundations and challenges of enforcing this right, emphasizing its critical role in addressing global displacement crises.

The study identifies inconsistencies in how the right of return is applied across instruments like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Geneva Conventions. Key questions include: Who qualifies? When is it binding? What limitations are permissible? While some frameworks broaden protections to generational refugees, others restrict them, reflecting the lack of a unified approach.

A significant finding is that the right of return was not fully recognized as CIL until the 1990s, despite earlier references in international law. Historical examples, such as repatriation in Bosnia and Rwanda, highlight both the potential for and obstacles to implementing this right, including legal, economic, and security challenges.

The study calls for stronger legal frameworks, including a new UN Human Rights Committee general comment on ICCPR Article 12(4) and an additional protocol to the 1951 Refugee Convention, to clarify protections and address modern challenges. It argues that proportionality in limiting this right diminishes across generations, with stronger claims for those directly displaced.

The research stresses the urgent need for a globally recognized legal structure to consistently enforce the right of return, balancing state sovereignty with displaced persons’ rights. As displacement crises escalate, establishing clear legal mechanisms is essential to protect individuals, support repatriation, and uphold international law’s credibility.